Foundations of Precolonial Okhoa Society

(General Anthropology, Political Science, Legal Anthropology, Keylic Indigenous Studies, History, Sociology)

Academic Magazine

Explore

I. Introduction: The Early Okhoa World

Pre-contact Okhoa society emerged within coastal fjords, marshlands, and rugged coastal margins of western Keyli. An ecological mosaic that demanded cooperation, seasonal mobility, and a deep understanding of land-based subsistence. These landscapes, marked by shifting waterways, dense boreal forests, and unpredictable southern storms, shaped a culture that relied heavily on collective labor and intergenerational knowledge. Communities organized themselves around shared responsibilities such as irrigation maintenance, fish-weir construction, rotational cropping, and seasonal hunts, all of which reinforced the bonds between kin groups.

In this era, before 837 CE, no truly centralized state apparatus existed in Okhoa lands. Authority flowed instead through an intricate network of clans that functioned as political assemblies, extended families, economic cooperatives, and cultural custodians. Each clan acted as a sovereign community, negotiating its own internal affairs and managing its territorial boundaries. Some clans forged loose alliances for trade or mutual defense, but none rose to the level of an overarching confederacy. Rivalries, diplomatic marriages, temporary pacts, and ritualized competitions shaped relations between these groups, creating a political landscape defined by shifting balances of power rather than permanent hierarchies.

Despite the absence of a singular state, the clans shared a remarkably cohesive cultural framework. Their rites surrounding leadership, inheritance, conflict resolution, and social identity reflected a shared civilizational logic. One governed by reverence for ancestry, moral reciprocity, and a belief that legitimate rule required constant, visible engagement with the people. Festivals, clan gatherings, market days, and interclan councils reinforced these cultural ties, ensuring that while Okhoa was politically decentralized, it was rarely culturally fragmented.

This blend of autonomy and shared tradition produced a society that valued both independence and interdependence. Clans saw themselves as distinct, yet intrinsically part of a larger world. Their stories, symbols, and communal philosophies formed a durable cultural backbone that endured well into the age of colonialism. In many ways, the foundations of Okhoa identity: its political pluralism, layered social structures, and emphasis on ritual legitimacy, were already fully articulated long before foreign ships appeared off their shores.

Communal Architecture and the Yggdrӕja Complex

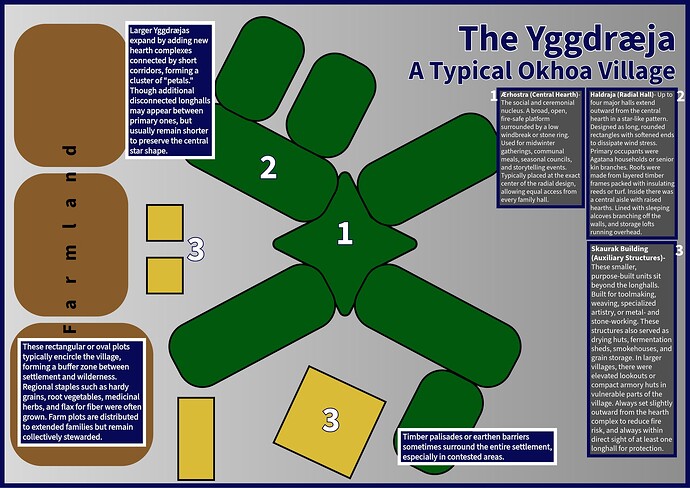

Settlements in the early Okhoa world were organized around a distinctive architectural pattern centered on the Yggdrӕja, the primary residential and ceremonial structure that shaped both daily life and collective identity. These complexes served as the physical embodiment of clan cohesion. Community spaces where kinship, labor, ritual, and governance converged.

At its core, each Yggdrӕja contained a vast central hearth, a circular stone-lined fire pit large enough to accommodate dozens of people during winter gatherings. This hearth was more than a source of warmth though. It served as a venue for seasonal feasts, trade negotiations, midwinter rites, and oral assemblies where elders recited ancestral genealogies or recounted the first migrations into the Okhoa fjords. Children learned social expectations here, apprentices received their ceremonial introductions, and visiting traders or envoys were welcomed with ritual hospitality. The central hearth thus functioned simultaneously as council chamber, religious space, dining hall, and repository of communal memory.

Radiating outward from this hearth were up to four permanent residential halls, each reserved for the Agatana lineage or for prominent professional families such as master shipwrights, smiths, or renowned merchant households. These adjoining halls varied in size depending on the clan’s prosperity, with wealthier or more populous settlements building elaborate multi-room structures of timber beams, packed earth flooring, and insulated turf roofing. In less stratified or smaller villages, the attached halls were simpler but retained the same symbolic relationship, with proximity to the hearth denoting prestige and responsibility. Reinforcing the expectation that those closest to power were also closest to service.

As populations expanded, clusters of secondary dwellings, usually smaller timber or wattle structures, were added incrementally to form a ring or partial crescent around the central complex. These additional buildings housed extended kin, professional lineages, visiting artisans, and at times, seasonal workers drawn from allied clans. The organic growth of these clusters produced villages that felt simultaneously planned and alive, with paths worn by generations of daily movement between homes, workspaces, and common areas.

In major settlements, particularly those located on rich floodplain terraces or coastal trade junctions, the scale of construction expanded dramatically. Multiple Yggdrӕja hearths might be built in close proximity, creating a large, unified courtyard at the center of the village. Such settlements often held cross-clan gatherings, competitive festivals, and semi-annual markets that attracted traders from far beyond Okhoa cultural boundaries. Oral tradition describes these multi-hearth courtyards as places where alliances were forged, marriages arranged, and disputes resolved before they could escalate into feuds.

Protection also played a role in settlement design. Many larger or frontier-facing villages enclosed their Yggdrӕja complexes within earthen ramparts, post walls, or palisaded wooden rings. These fortifications served practical defensive purposes such as deterring predators, bandits, and opportunistic raiders, but also carried ritual significance. The walls symbolized the clan’s guardianship over its hearths, its ancestors, and the spiritual equilibrium believed to radiate from the central fire. Crossing the boundary into such a settlement was often accompanied by small gestures of respect, such as touching the entry post or offering a short recitation to the local spirits of protection.

Taken together, the Yggdrӕja system provided more than shelter, it structured social life, reinforced kin hierarchies, and embodied the clan’s unity in physical form. In an environment defined by harsh Winters, storm-battered coasts, and dense forests, these architectural traditions anchored the community, offering both stability and a shared sense of identity. The layout of the Yggdrӕja mirrored the very nature of Okhoa society: decentralized yet cohesive, locally autonomous yet culturally unified through common forms, rituals, and social expectations.

II. Clan Governance and Social Hierarchy

At the summit of every clan stood the Agatana, the ruling lineage that embodied both political authority and spiritual continuity. Their mandate encompassed governance, land allocation, dispute settlement, oversight of trade routes, and the maintenance of ceremonial traditions tied to clan identity. Although numerous family members within the Agatana might hold informal or situational influence— particularly respected elders, accomplished warriors, or renowned negotiators— formal power remained concentrated in the hands of the Agatana Pri.

The Agatana Pri served simultaneously as executive leader, moral exemplar, and ritual figurehead. While it was common for this role to fall to a senior member of the ruling line, neither age nor birth order was a strict determinant. Instead, the position required a combination of perceived wisdom, strength of character, and ritual legitimacy. The Pri’s authority rested heavily on their ability to preserve harmony within the clan and to navigate the delicate interplay between tradition and daily governance. Severe winters, interclan tension, or internal strife occasionally propelled younger or other less conventional candidates into the role, but such transitions were themselves ritualized, ensuring continuity even amid uncertainty.

Although governance within clans was fundamentally autocratic, it was rarely totally isolated from the broader population. Many clans, especially those spanning multiple settlements or fjords, maintained structured means for listening to common folk. The most prominent of these was the nine-year “choosing” to select the Agatana Asius. These gatherings usually took place at ancestral centers such as ancient burial mounds, sacred groves, river confluences, or stone enclosures tied to mythic clan origins.

The Asius served as a sanctioned intermediary, empowered to convey grievances, propose policy needs, and advocate for vulnerable groups such as peasants, apprentices, or widowed households. Their role did not diminish the Pri’s supremacy, but it created an avenue for communal influence that tempered autocratic excesses. First documented among the island clans and the populous Urbhala-sin domain, the institution spread steadily across the Okhoa world as clans recognized its utility in managing disputes and preventing social unrest. Its growth is now regarded by scholars as one of the earliest indicators of proto-representative governance among the Okhoa.

Despite these mechanisms, the Agatana Pri’s authority remained absolute. They could overturn any council decision, revoke privileges, or reorganize landholdings without formal challenge. The only permitted check on this power lay in a single severe recourse: Faffëyakk, a lethal duel meant to resolve crises of legitimacy.

Faffëyakk was an ordeal steeped in symbolism. Combatants wielded six daggers carved from river ice— a material chosen for its impermanence and fragility. The breaking of blades during combat served as a reminder that leadership, like ice, was both powerful and dangerously transient. Participants were typically the Pri and their challenger, though in rare cases the challenger appointed a champion.

Historical accounts suggest that invoking Faffëyakk was extraordinary, occurring only when a clan’s confidence in the Pri had collapsed or when factional conflict had become irreconcilable. Most clans considered the duel a tragic necessity, a last resort to restore social balance rather than an acceptable political tool. The infrequency of Faffëyakk underscored the stability of most ruling families, who relied on ritual authority, kinship diplomacy, and communal expectations to maintain their legitimacy.

Through these layered systems of status, ritual, and political practice, pre-contact Okhoa governance maintained a delicate equilibrium— combining the unbroken authority of the Agatana with channels for communal influence that helped sustain cohesion across generations.

III. Social Strata and Mobility

The Professional Echelon

Below the ruling class stood a wide and diverse professional stratum, one of the most dynamic and socially influential elements of pre-contact Okhoa society. This echelon encompassed merchants involved in interclan trade, educators who preserved oral histories and technical knowledge, master artisans responsible for specialized crafts, and warriors who protected clan interests or represented their people in ritual combat. Although grouped together as a single category, these professions varied significantly in prestige, mobility, and political leverage.

Merchants functioned as the connective tissue of the Okhoa world. Skilled in negotiation, risk management, and the navigation of the land, they transported goods ranging from salt and iron to dyes, medicinal herbs, textiles, and ritual objects. Because successful trade demanded trust across clan boundaries, merchants often became informal diplomats. Many Agatana relied on them for intelligence about neighboring clans, market conditions, and external threats. An aspect that elevated their social standing well beyond simple economic activity, and offered an extra layer of protection.

Educators, though smaller in number, held a unique cultural importance. They maintained genealogies, ceremonial protocols, agricultural knowledge, and the oral records of clan events. In communities without a written script, these individuals were essential custodians of identity and continuity. Trained from childhood through long apprenticeship, educators often formed long-term partnerships with the ruling family, advising on ancestral precedent, ritual timing, and the interpretation of omens.

Articifers, including smiths, stonecutters, shipwrights, and producers of important ritual goods, enjoyed high prestige due to the rarity and difficulty of their skills. Some crafts were considered semi-sacred, particularly the production of artefacts used in religious ceremonies or the carving of ancestral Yggdrӕm. Articificers were typically exempt from certain communal labor obligations and were compensated through food shares or land privileges, further reinforcing their elevated position.

Warriors, while sometimes romanticized in later Okhoa tradition and contemporary media, were primarily professionals bound by strict codes of conduct and clan responsibility. Their role extended beyond battle, tasked with patrolling caravan routes, enforcing rulings made by the Agatana, and participating in interclan ceremonies that required ritual displays of martial strength. Warriors who proved themselves in conflict could rapidly ascend in influence, sometimes earning honorary ties to the Agatana or being granted Vüfirӕm, large sums of interclan currency or some other valuable commodity.

Because entry into this broad professional category was based on demonstrated expertise rather than ancestry alone, it represented the most socially and politically mobile layer of Okhoa society. A laborer who demonstrated exceptional ability in trade, skilled craftsmanship, or military service could ascend to this stratum over time. Such upward mobility was not only possible but encouraged, as clans benefited from having their most capable members in positions of power and responsibility.

The influence of this class was visible in clan governance as well. While the Agatana held ultimate decision-making authority, professionals often formed the informal advisory circle surrounding the Pri. Their knowledge of economic cycles, conflict patterns, resource availability, and interclan relations made them indispensable. In some clans, especially those strategically positioned along coastal or accessible inland trade routes, the professional class became particularly powerful. Powerful enough to shape major policy decisions and even to influence the selection of the Agatana Asius via electioneering, or more legitimate means. Regardless, this was a dynamic and skilled stratum that helped maintain both the economic health and cultural sophistication of Okhoa society, acting as a crucial intermediary between the ruling elite and the broader body of clansfolk.

Farmers, Apprentices, and Clerics

The middle strata of traditional Okhoa society consisted of subsistence farmers, fisherfolk, herders, and other essential food producers whose labor sustained the daily life of their clans. Though not as wealthy or politically influential as the professional echelon above them, this group formed the economic backbone of the colonization Okhoa world. Their status was respected, if modest, and their influence fluctuated depending on a clan’s size, terrain, and political culture.

Farmers tended small plots that typically belonged not to individuals but to extended households or the clan as a whole. They cultivated hardy grains, tubers, and legumes suited to the western Keylic climate, rotating crops according to inherited ecological knowledge. Because food stability was central to clan survival, skilled farmers— especially those who mastered irrigation methods or soil management— earned quiet but steady prestige. In some clans, elder farmers held informal advisory roles during seasonal planning.

Fisherfolk played an equally critical role, particularly in coastal and island communities. Their expertise in tides, weather patterns, and fish migrations made them indispensable. Fishing crews were usually organized by kin groups, and successful captains could gain local renown. While they rarely held formal political sway, their livelihoods created strong communal networks that sometimes influenced clan discussions, particularly in maritime clans whose economies revolved around coastal resources.

Herders and pastoralists, though far fewer in number, contributed meat, hides, and transport animals. They often lived on the outskirts of clan territories, giving them a reputation for independence and resilience. Their liminal position placed them outside the center of political life yet made them vital scouts and guides during interclan movements or seasonal migrations.

Alongside these food producers stood the clerics, a group sometimes misunderstood in later Okhoa historiography. These were not religious figures but rather recordkeepers, archivists, and ceremonial documenters. They maintained clan histories, tallied resource distributions, tracked kinship lines, and preserved ritual precedents. Clerics served as the institutional memory of the clan. Although their authority did not carry the same weight as that of educators or master artisans, the Agatana relied on them to legitimize decisions and maintain internal order. In politically complex clans, particularly those with multiple jurisdictions, clerics wielded subtle but real influence by controlling access to genealogical and legal knowledge.

Apprentices rounded out this stratum. Most were youths beginning long periods of training under master craftspeople, clerics, healers, shipwrights, or merchant families. Apprenticeship was a pivotal stage of Okhoa social development, marking a young person’s transition from general communal labor to specialized skill-building. Although apprentices themselves held little status, their future potential was highly regarded. Families often made significant sacrifices to place promising children in reputable apprenticeships, seeing it as a path to upward mobility and, eventually, entry into the professional echelon.

Despite their essential contributions, the political leverage of this middle group varied widely. In some more egalitarian clans with strong communal traditions, respected farmers or clerics might speak at gatherings or influence the selection of the Agatana Asius. While in more stratified or aristocratic clans, their roles were strictly circumscribed, and they participated only indirectly in political life.

Nevertheless, their work sustained every aspect of Okhoa society, and their steady presence formed the bridge between the everyday experiences of the clansfolk and the ambitions of the ruling elite.

The Peasantry and Social Disparity

In clans with more rigid internal hierarchies, a distinct peasant class emerged among the general laborers, consisting of those who had neither mastered a specialized craft nor secured a professional role within the clan. Although their daily work often paralleled that of lower-level professionals or apprentices, the key difference lay in the absence of formal recognition. A person became labeled a peasant not because their labor lacked value but because it lacked distinction within the clan’s cultural framework.

This status carried significant social consequences. Peasants were frequently perceived as individuals who had not “proven” themselves in any particular skill, making them socially unremarkable and limiting their ability to cultivate influential relationships. In stratified clans, especially those with powerful Agatana or wealthy merchant circles, peasants risked being overshadowed by the prestigious accomplishments expected of other clansfolk. Community life, which prized not only hard work but visible competence, tended to sideline those who could not demonstrate specialized expertise.

Despite these limitations, peasants were vital to the functioning of the clan. They filled the labor gaps that specialists left behind, taking on essential but unglamorous tasks such as maintaining irrigation ditches, gathering firewood, mending communal structures, or transporting goods. When seasonal demands surged, peasants also assisted in the harvest, caravan preparation, and large hunts.

Peasants formed the bulk of the workforce that enabled clan survival, but politically their influence was narrow, but not nonexistent. Although excluded from Agatana deliberations and rarely consulted on policy, most clans granted peasants the right to vote in the periodic election of the Agatana Asius. This small but significant concession allowed common laborers to assert a collective voice, especially in clans where the Asius was expected to champion broader concerns such as equitable resource distribution or labor conditions. When large peasant blocs mobilized, usually around issues of food security, land use, or unfair tribute requirements, their votes could meaningfully shift who represented the clan’s common folk.

Still, such opportunities did little to alleviate the broader social disparity. Peasant status often became self-reinforcing as the limited recognition restricted access to training, and limited training reinforced their lower status. Some individuals broke free by mastering a new skill later in life, a path that Okhoa tradition strongly encouraged but which required time and opportunity many lacked. Most peasants remained in the same social tier across generations, contributing to a subtle but persistent class divide that shaped internal clan dynamics long before foreign contact.

Even so, the presence of the peasantry reflected a distinctive feature of Okhoa society: mobility was possible, even if unbalanced, provided one could demonstrate skill, reliability, or exceptional service. This belief, which remains deeply rooted in Okhoa cultural ethics, prevented the peasant class from becoming rigidly hereditary and lent a degree of flexibility to social structures that might have otherwise hardened into castes.

The Lowest Strata: Slaves and Outlawed Criminals

At the fringes of Okhoa society lay two groups whose status placed them outside the protections ordinarily afforded to clansfolk: slaves and outlawed criminals. Although the Okhoa world did not practice slavery at the vast hereditary scale seen in some empires, several forms of bondage and punitive servitude did exist. These instances were shaped by clan law, wartime necessity, and moral codes that emphasized restitution over simple retribution.

Slaves were rarely taken in conventional warfare, as Okhoa clan conflicts tended to be brief, seasonal, and governed by strict honor customs. However, in periods of famine, prolonged feuding, or when rival clans committed grievous offenses, captives might be taken to compensate for labor losses or territorial damage. These war captives were considered temporary property of the Agatana or the warriors who had taken them, though their treatment varied widely between clans. Some were integrated into household labor, while others worked in agricultural or construction tasks until formal release or ransom.

Far more common were criminal-bond laborers, individuals who had violated clan law in ways deemed disruptive but not irredeemable. Crimes such as theft, fraud, ritual violation, or unregulated violence— excluding homicide— often resulted in a term of compulsory labor “for the people’s good,” as preserved in several early clerical records. These sentences were carefully measured in days, months, or years and were not intended to degrade the individual permanently. When completed, some individuals regained partial social standing, though reintegration depended heavily on the person’s reputation, the gravity of their offense, and the willingness of more influential clansfolk to advocate on their behalf and accept them back into common life.

This made reintegration possible, but difficult and the newfound status was fragile. Former bond laborers frequently bore social suspicion, and while they could legally return to ordinary life, few ever rose into the professional echelon or held positions of responsibility. In some clans, upon completing their term, individuals participated in public cleansing rituals intended to symbolically restore their place among their people. Success depended not only on personal conduct but also on the forgiveness of injured parties and the broader clan’s willingness to welcome them back.

Yet there remained offenses such as treason, murder without cause, or grave sacrilege that demanded a more severe sanction: Discommendation, the ultimate form of punishment in Okhoa society. Discommendation was not merely exile, it was a complete civic death. Those condemned were marked with a scalding hot iron on the left cheek, burned with a symbol recognizable across the Okhoa world. This mark, identical in every clan, ensured that the disgraced could never conceal their status or seek sanctuary without revealing their past.

Once branded, a person was driven from clan territory and declared outside the law and the protection of all kinship networks. They could not marry, hold land, enter into contracts, or appeal for justice. Any clan that sheltered a discommended individual risked severe diplomatic consequences, including the possibility of retaliatory raids or ritual sanctions. As a result, most exiles found no community willing to accept them. As a result, few survived long. The plains and forests beyond clan boundaries were unforgiving, with predators, harsh winters, and few accessible water sources. Those who did endure often banded together with other exiles, forming desperate, itinerant groups that raided caravans, isolated farms and villages, and remote shrines. These bandit gangs became a persistent threat in the hinterlands and feature prominently in later Okhoa oral histories, simultaneously feared, pitied, and moralized as cautionary tales.

Despite the severity of Discommendation, Okhoa oral traditions emphasize that it was used sparingly, reserved only for those whose actions threatened the clan’s stability, spiritual balance, or honor. Its existence served as a grim reminder of the fragility of social belonging in a world where kinship was the cornerstone of survival.

Sections IV and V below