PART 2: The Taizong Empire: The Huayu Language, The Age of The White Lotus, Huwanese Global Expeditions, War of the Red Moon (1480 AD - 1781 AD)

The Huayu Language

Among the enduring legacies of the Taizong Empire was the creation and widespread adoption of the Huayu language, which became the first standardized language for the newly unified empire. Commissioned by Emperor Manga Taizong of the 3rd royal lineage, alongside linguist Jou Youguang, the Huayu language played a crucial role in fostering unity and communication across diverse regions.

Prior to the development of Huayu, the empire grappled with a multitude of dialects and regional scripts, making governance and communication challenging. Ethnic differences, such as varied pronunciations and intonations, compounded the linguistic complexity, hindering effective communication. Emperor Manga’s personal experience, where his bride from Rong province struggled to comprehend the Lian-style dialect spoken at the imperial court, highlighted the urgent need for a standardized language.

Drawing from the expertise of scholars, monks from the Khuu order, and insights from imperial and foreign sources, Jou Youguang crafted the Huayu script. This new alphabet, consisting of 61 characters categorized into back vowels, front vowels, consonants, and indifferent consonants, aimed to streamline communication while minimizing confusion. Notably, Huayu eliminated intonation in favor of a diverse range of vowel types and a meticulous vowel harmony rule. The script’s design prioritized ease of writing, accommodating both brush and tablet formats, and featured an additive vocabulary to enhance clarity.

Despite facing initial hurdles, such as the lengthy two-century period required for complete implementation, Huayu gradually entrenched itself in the daily lives of empire inhabitants. Its standardized structure played a pivotal role in promoting literacy among the general population, serving as a unifying force that bridged linguistic divides across diverse regions of Huawan.

Furthermore, the establishment of Huayu as the official language of administration and education streamlined communication and fostered a shared cultural identity among Huawanese citizens. Its adoption facilitated the dissemination of knowledge, enabling the spread of literature, philosophy, and scientific advancements throughout the empire. Additionally, Huayu’s standardized grammar and vocabulary enhanced efficiency in government bureaucracy, ensuring clarity and consistency in official documents and decrees.

The Huayu script has then evolved to other brushstroke types as well. Mainly oracle bone script, seal script, clerical script, cursive script, semi-cursive script, and standard script. Even with the introduction of the australized script in 1965, traditional Huayu script remains widely utilized, underscoring its enduring popularity and cultural significance. As a testament to its enduring legacy, Huayu continues to be revered as a symbol of unity and cultural pride among present-day Huawanese communities.

The Age of the White Lotus

Rai-Na Taizong was born to Emperor Manga Taizong and Royal Consort Wakana Cheon in 1527. According to the disputed text of Hwata Tiga, after the tragic death of her half-brother Emperor Kai Taizong and the entire royal family during a diplomatic visit to Bailtem, Rai-Na Taizong inherited the title of Great Empress of Huawan. At just 15 years old, Rai-Na was not originally in line for the throne.

Emperor Manga Taizong had appointed his firstborn, Kai Taizong, as Emperor. The succession plan then considered Empress Jaana Taizong’s brother, Kim Tanxian (brother-in-law to Emperor Kai Taizong), as next in line. However, upon Manga Taizong’s deathbed, Rai-Na made a heartfelt plea to her father, arguing that she had as much right to compete for the throne as Kim Tanxian. Impressed by her determination, Manga Taizong amended his will to include Rai-Na as the next in line of succession.

The chronicle of Hwata Tiga is heavily debated among historians. Emperor Manga Taizong was known to be a staunch womanizer, and Rai-Na was actually born from the Royal Consort as well as her mother being a woman outside the imperial harem. While it was not unusual for women to wield power in Huawan, the idea of a female ruler sitting on the Taizong throne was controversial. An alternative narrative suggests that Rai-Na’s placement in the line of succession was a strategic move to placate the House of Cheon, one of the four royal houses that commanded Huawan’s finest navy.

This theory posits that the House of Cheon and their loyalists may have orchestrated an attack on the imperial ships after the diplomatic visit, resulting in the deaths of Kai Taizong and other potential challengers to Rai-Na’s coronation. However, the theory was widely disputed because the ascension of Rai-Na as Empress did not elevate the House of Cheon, rather, it faced near dissolution after the famous “White Lotus Expeditions Decree.”

Despite these controversies, Rai-Na Taizong was coronated in the Royal Palace of Lian in 1542, just two months after her 15th birthday and still in tremendous grief from her loss. She became the 6th monarch of the Taizong dynasty and the first of only two female monarchs in its history. Her rise to power marked a significant shift in the Taizong era, characterized by her resilience and the contentious circumstances surrounding her ascension.

The decision was not accepted by everyone, and as a result, some court officials planned an uprising in order to stop her from being crowned. Imperial Minister Achan Chilsuk and Royal Consort Boram planned a rebellion. But their plan was discovered by the royal Avashi Guardians and suppressed early on. As punishment, Royal Consort Boram was beheaded in the central market of Lian along with her entire family. Minister Achan was able to escape and ran to the Huawan-Valkyrian border. However, he left his wife and decided to return after exchanging clothes with a boar hunter. Upon his return, he was arrested by royal lancers waiting for him at his home, and was later executed by boiling oil.

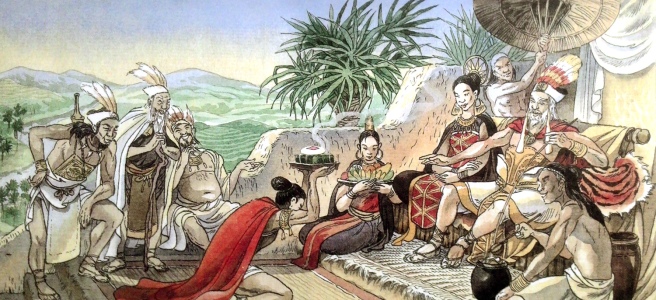

Empress Rai-Na’s primary concern was the livelihood of her people. Right after her coronation, she sent imperial messengers throughout the empire to announce her policies. Royal inspectors were dispatched to improve the care of widows, orphans, the poor, and the elderly. In the same year, she sent a diplomat to pay tribute to the Emperor of Karnetvor with an abundance of silk and tea. However, the Emperor refused to acknowledge Rai-Na as a ruler because she was a woman and of lower birth than the Taizong.

Officials noticed that the new empress differed from previous queens in her choices and determination. She avoided lavish parties, rarely commissioned extravagant fashions from the royal ateliers, and almost never hosted social gatherings unless required for political reasons. Expected to act as an icon for Huawan’s high society, the monarch rejected this role. Instead, she spent her time reading books written in Huayu and Valkyrian characters, typically reserved for aristocratic men. A studious character, she furthered her own education in history, science, politics, philosophy, and religion.

Under Empress Rai-Na’s enlightened rule, the empire experienced a renaissance of cultural and intellectual achievement. The imperial court became a beacon of learning and creativity, attracting scholars, artists, and thinkers from across Cordilia and beyond. Empress Rai-Na’s patronage of the arts and sciences knew no bounds, with grand projects and scholarly endeavors receiving generous support from the imperial treasury.

In the second year of her reign, Empress Rai-Na commissioned the Heavenly Towers of Maa, astronomical observatories used to help farmers with crop rotations. She also announced a year of tax exemption for peasants and reduced taxes for the middle class, winning the people’s support and strengthening her position against the opposition of the male aristocracy.

To gather the support of the Khuu, Empress Rai-Na commissioned the construction of a 100-meter tall pagoda for spiritual security and to calm her people. Despite opposition from the imperial court concerned about the treasury, the Empress continued with the plan, believing a work of religious devotion would bring her people together. The pagoda, known as the Dagon Temple, housed scriptures from Cordilia and served as a center for the Khuu faith. Annually, Empress Rai-Na would visit the tower to pray for a good harvest.

Rai-Na’s astute acumen in industrialization massively expanded both agriculture and manufacturing in the empire. Her decrees to improve industrial heartlands reinforced the Great Golden Road, boosting Taizong influence by exporting fancy fruits, medicine, silk, jewelry, furniture, pottery, and monastic scrolls. Even after her reign, Taizong goods were coveted by foreign monarchs and high society, for Empress Rai-Na believed the grandeur of the Taizong was an exportable commodity.

One of her unique exports was tea. She decreed the founding of the Imperial Tea Holdings (now TianTang Tea Holdings), which played a significant role in spreading tea in the 16th century. Tea, credited with medicinal properties, complemented the ornamental objects of Taizong origin or inspiration, fashionable in the 16th century.

Uniquely, she also exported scholars and talent. Taizong architects, monks, physicians, and philosophers traveled alongside caravans across Cordilia. The tradition was so respected that an old Taizong saying emerged: “pursue knowledge and prosperity as far as Stoinia,” the farthest extent of the Golden Road.

Huawanese Global Expeditions

Perhaps one of Empress Rai-Na’s most famous acts was her extensive and powerful expeditionary navy. Believing that the influence of her empire could be placed through a strong commercial enterprise, she knew that diplomatic and commercial expeditions are needed.

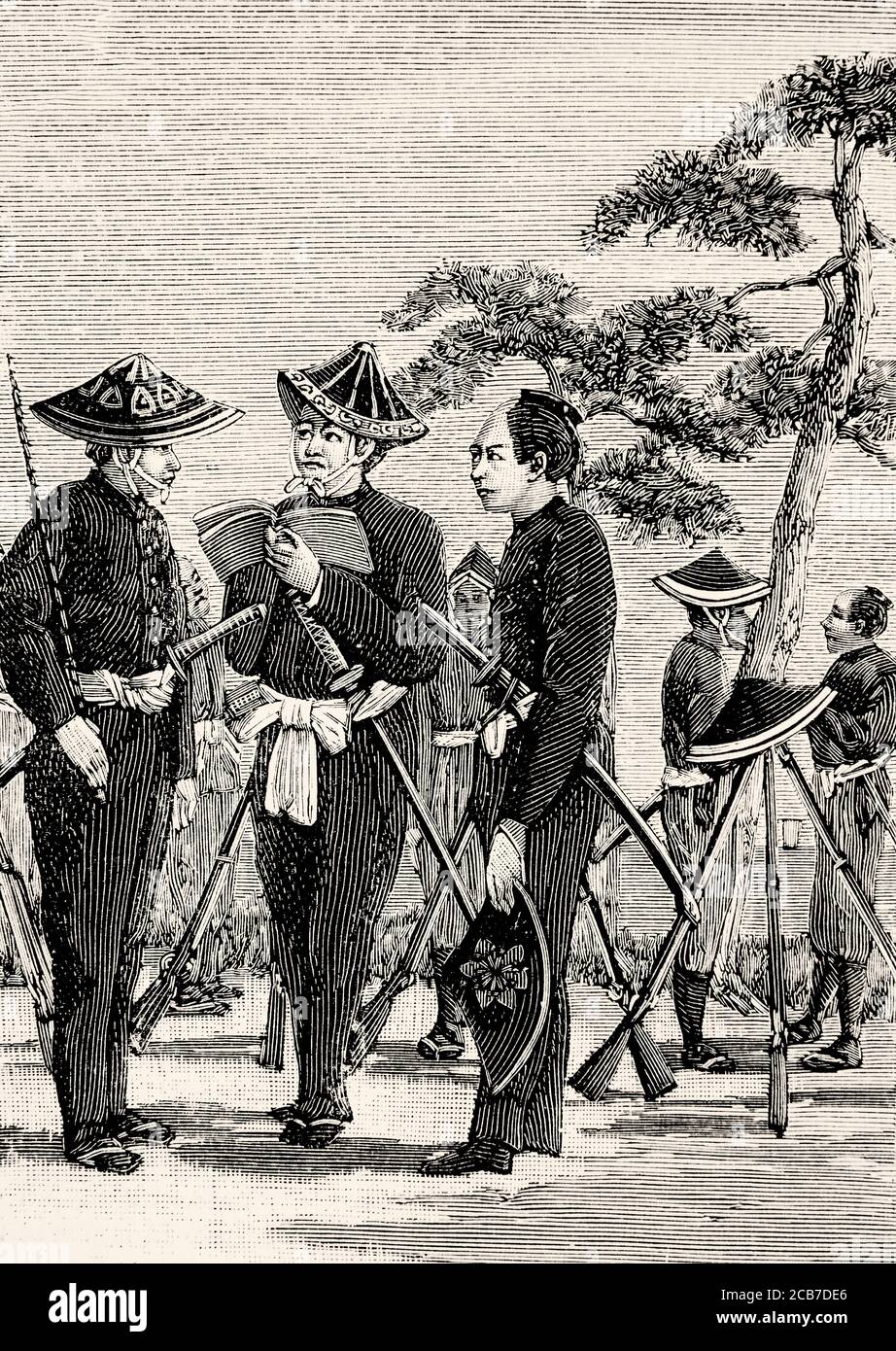

The White Jade Dragon Expeditions Decree, posted in 1550, was a monumental declaration that marked the beginning of an ambitious era of exploration, diplomacy, and trade expansion under Empress Rai-Na Taizong. Empress Rai-Na, recognizing the importance of establishing Huawan as a dominant maritime power, aimed to extend the influence of the Taizong Empire across the seas. The decree outlined a series of exploratory and commercial voyages, symbolized by the banner of the White Lotus, an emblem of purity, strength, and wisdom. She gathered that Huawanese seafarers, let it be mercenaries, tradesmen, marines nor pirates shall sail under the White Lotus.

The decree called for the construction of a formidable fleet of ships equipped for long voyages. These ships, known as the “White Lotus Fleet,” were designed with the latest advancements in shipbuilding technology, combining speed, durability, and cargo capacity. These floating cities included warships for protection, merchant vessels for trade, and specialized ships for scientific and cultural missions. Although she had personally commissioned the vessels to be commandeered by House of Cheon, the liquidation of the house’s naval influence into the imperial navy had almost disintegrated the Cheon house.

The primary objectives of the White Jade Dragon Expeditions were threefold:

-

Expansion of Trade Routes: Empress Rai-Na sought to establish new trade routes that would connect Huawan to distant lands. The expeditions aimed to secure lucrative trade agreements, bringing exotic goods, spices, precious metals, and other commodities back to Huawan. These new routes would also facilitate the export of Huawan’s finest products, including silk, tea, porcelain, and scholarly works, enhancing the empire’s economic prosperity. They are also instrumental in establishing trade outposts of the Huawanese trading companies.

-

Diplomatic Relations: The expeditions were tasked with establishing diplomatic relations with foreign kingdoms and empires. Empress Rai-Na understood the importance of alliances and sought to build a network of friendly states that would support Huawan’s interests. Diplomatic envoys aboard the White Lotus Fleet carried gifts and letters of goodwill, seeking to foster peace and cooperation.

-

Cultural and Scientific Exchange: Empress Rai-Na, a patron of knowledge and culture, saw the expeditions as an opportunity for intellectual and cultural exchange. Scholars, artists, and scientists accompanied the voyages, eager to learn from other civilizations and share Huawan’s advancements. These exchanges enriched Huawan’s own cultural and scientific landscape, fostering innovation and mutual understanding.

The first wave of the White Jade Dragon Expeditions set sail from the bustling ports of Hai Lan, carrying with them the hopes and ambitions of the Taizong Empire. The fleet traveled to the far reaches of Cordilia and beyond, visiting the courts of powerful monarchs and exploring uncharted territories. The voyages were not without challenges, facing treacherous waters, hostile encounters, and the rigors of long-distance travel. However, the perseverance and skill of the fleet’s commanders and crews ensured their success.

One of the most notable achievements of the White Jade Dragon Expeditions was the establishment of a thriving trade network that stretched from the eastern shores of Cordilia to the distant lands of Stoinia, Sedunn, Kai-Fa, and Montacia. Huawanese merchants became a common sight in foreign markets, and the exotic goods they brought back fueled a period of economic boom in Huawan. The influx of wealth allowed Empress Rai-Na to fund further cultural and scientific endeavors, solidifying her legacy as a ruler who brought prosperity and enlightenment to her people.

Diplomatically, the expeditions forged strong alliances with several key states, including the Aegians, the Karnetvorians, The Valkyrians, the Garan State, The Yttrians and the Mitalldukish and Krautali. The flow of goods from Golden Road states would flow along with the Jade fleet, and ensure loyalty to the Taizong court. Even the Karnetian Imperial court, which had initially refused to acknowledge Rai-Na as a ruler. Over time, the Karnetvor Emperor was persuaded by the skillful diplomacy and the undeniable benefits of trade with Huawan. Other states followed suit, and Huawan’s influence grew steadily across the region.

The cultural exchanges facilitated by the White Jade Dragon Expeditions had a profound impact on Huawanese society. New ideas, artistic styles, and scientific knowledge flowed into the empire, sparking a renaissance of creativity and intellectual growth. Empress Rai-Na’s support for these exchanges reinforced her commitment to fostering a vibrant and enlightened society.

Empress Rai-Na Taizong’s reign, marked by the visionary White Jade Dragon Expeditions, transformed Huawan into a global maritime power and a beacon of culture and knowledge. Her legacy as a ruler who balanced wisdom with ambition, and who valued both her people’s welfare and the empire’s grandeur, endured long after her time. The White Jade Dragon became a symbol of Huawan’s golden age, a testament to the empire’s far-reaching influence and the enduring spirit of exploration and discovery.

But perhaps the crowning achievement of Rai-Na’s rule was in her longevity, a long period of peace and stability. The chronicle of the Hwata Tiga wrote that with her own blood and ink, Rai-Na wrote on a scroll in front of her court, then with her bleeding palm presented the scroll which read “Yi Li, Zhi He” or “Peace through power.” Believing the best way to ensure a period of peace would be to hold a strong banner and a strong army, and the historical scroll was dubbed “The decree of the white fox” and set a principle of Huawanese foreign policy in futures to come.

In line with the philosophy of “The decree of the white fox”, the expeditions also served as a deterrent against potential adversaries. The display of Huawan’s naval strength discouraged hostile actions and ensured that the empire’s interests were protected. This strategic approach allowed Huawan to maintain peace and stability, reinforcing its position as a dominant and influential power in the region.

One of Huawan’s major alliances was with the alliance of the Elbonian Empire. In exchange for the empire’s support for the Golden Road its spread and subjugation of the Taizong’s competitors, White Lotus Navy privateers would serve the Elbonians in establishing a naval trade route through Moellia and Valkyria as well as undermine her enemies. The alliance would echo for centuries until the end of the Taizong.

The Banner of the White Lotus flowed in many foreign states of South Pacifica as a sign of Huawanese, and more importantly, Taizong, influence. The White lotus were synonymous to enlightenment and the fashionable Huawanese identity, and bearing such a standard was The Great Empress Rai-Na Taizong, who chroniclers dub as “The White Lotus.”

Empress Rai-Na lived to the age of 84. She was married twice, had two kids yet mothered ten more, all whose lineage could be traced to Huawanese famous characters, such as Tan Yanxian, who was the Mother of Huawanese Medicine. Even after her passing the Taizong empire experienced the peak of their success for nearly a century after, dubbed as “The Golden Age of the Lotus”

War of the Red Moon, and Fall of the Taizong

Until now, historians still debate the causes of the fall of the Taizong Empire. Some attribute it to the political shifts in the region at the turn of the 18th century, the industrialization of neighboring states, and the rise of republics that undermined Huawan. Others point to the culmination of cracks in the Taizong government’s armor and the growing dissent within its armies. However, a common consensus is that the Taizong Empire fell due to its complacency.

After the age of the White Lotus, the Taizong imperial court made numerous appeasements toward foreign trading companies operating in Huawanese lands, often to the detriment of the local populace. The deforestation of high-quality lumber, primarily shipped to Sedunn, and the diminishing influence over the Golden Road trade routes led to widespread discontent among the people.

Peaceful protests were often met with brutal violence, exacerbating the growing unrest. The Taizong government, once a beacon of enlightenment and progress, became increasingly authoritarian in its efforts to maintain control. The lavish expenditures of the imperial court contrasted starkly with the impoverishment and suffering of the common people, leading to a widening gap between the ruling elite and the masses.

One of the pivotal moments in the decline was the Taizong’s failure to adapt to the rapidly changing geopolitical landscape. As neighboring states embraced industrialization and republican ideals, Huawan’s traditionalist and isolationist policies rendered it vulnerable to external pressures and internal strife. The once-mighty navy, which had been the pride of the empire, fell into disrepair, and the trade routes that had brought prosperity now became channels for exploitation by foreign powers.

A significant blow came with the rise of the Bailtemmic East Cordilian Trading Company, which established a stronghold in the southern ports of Huawan. The company’s monopolistic practices and exploitation of resources created economic dependencies that further weakened the Taizong administration. The Taizong monarchs, increasingly out of touch with their people’s struggles, failed to counter these foreign influences effectively.

Discontent boiled over in 1716 as the famous “Plague of the Black Crow” ravaged the continent, accompanied by widespread famine. This led to a series of rebellions across the empire due to the ineffectiveness and corruption of political officials. These uprisings were fueled by widespread resentment towards the foreign trading companies, the corrupt local officials, and the oppressive policies of the Taizong court. The massacres in the sacred city of Aweiqinna filled the air with blood, gunpowder, and the wailing screams of victims, to the point that the moon appeared stained red with blood. Thus, the “War of the Blood Moon” began.

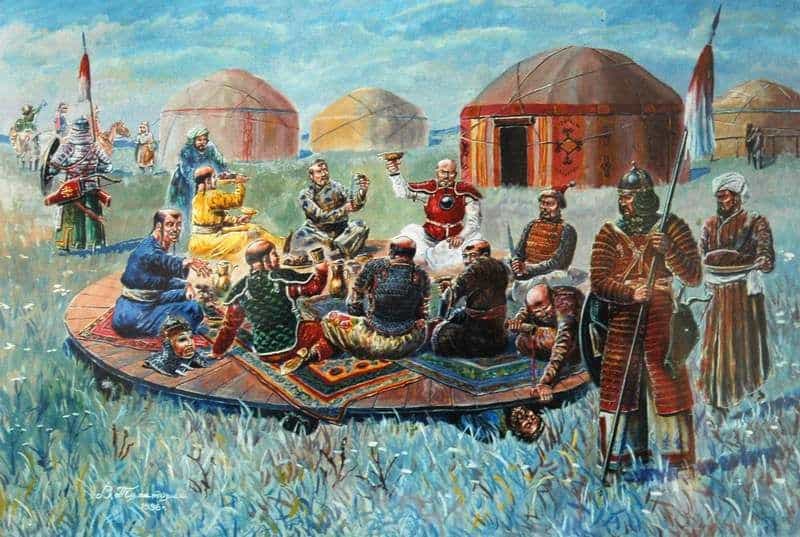

One of the most notable uprisings was the Four Banners Rebellion or the “Sitianwang,” led by a charismatic former monk, Mangling Mangsten, Baturu of The Fan, Kata Yan, Pirate Lord Gao Feng and Skilled tactician Gyara the Great. The rebellion, though initially suppressed, highlighted the deep fractures within the empire and the loss of faith in Taizong rule. Against the now disheveled Avashi order and the White Lotus, the banner of the four-colored peony became the symbol of the Sitianwang movement.

The nation plunged into a period of warring states for five years as the Taizong dynasty tried to consolidate power against the Sitianwang to no avail. The loss of support from the White Lotus navy and its replacement by a generation of pirates under Gao Feng dealt a blow to the Golden Road and Huawan’s influence, which remained irreparable for decades. Piracy rose to unprecedented levels, as the Sitianwang, believing with cause that foreign ships were attempting to restore stability to the oppressive Taizong, unleashed a terror on the oceans that Pacifica had never before seen.

In 1721, a catastrophic event shook the very foundations of the Taizong dynasty. The Great Fire of Lian, believed by some to be an act of arson by disgruntled factions within the empire, ravaged the capital city. Rebel forces marched into Lian where the last Taizong monarch, Emperor Hubu Taizong, made his final stand. Known as the Great Siege of Kabane, pirates stormed the palace by boat and took the city as fire rockets were launched. The imperial palace and many historical archives were destroyed, symbolizing the collapse of the once-glorious dynasty. In the wake of this disaster, the weakened Taizong government could not maintain order, and the court surrendered to the Sitianwang armies.

As Sitianwang troops marched into the Imperial Palace of Lian amidst cheering peasants and the sounds of wailing officials murdered by the crowd, Lady Mangling Mangsten set a single mountain peony flower drenched with Taizong blood on the steps of the burnt remains of the mausoleum of the last Masako Emperor, Mangsten Yuming.

Emperor Hubu Taizong was sentenced to execution amidst a cheering crowd of peasants, while his family was exiled to the southern pole colonies. The following weeks, Mangling Mangsten was appointed as the steward of the empire, later to be known as the Peocracy, and her, the Mother of the Peonies.

By 1725, the Taizong Empire had effectively ceased to exist as a unified entity. The fall of the Taizong marked the end of an era and the beginning of a period of turmoil and reconstruction for Huawan, known as the Age of the Red Lotus. Despite the dynasty’s demise, the legacies of its cultural and intellectual achievements continue to influence Huawan to this day.

.jpg&ehk=c2rd0K9l%2fEqUrV%2fvopBrqcIbF6T6E0op0xCrVLTe1Bg%3d&risl=&pid=ImgRaw&r=0)

.jpg&ehk=ShufjKMjmrzMalG%2bm7Uu00tp874hPot1mZ3EFY9oawQ%3d&risl=&pid=ImgRaw&r=0)